The Iroquois, also known as the Haudenosaunee or the “People of the Longhouse”, are an indigenous people of North America. In 1390 the five Iroquois-speaking tribes (Seneca, Oneida, Onondaga, Mohawk and Cayuga) of Ontario and upper New York State joined into a confederacy to keep the peace among themselves and to deal with trade and relations with other tribes. According to the legend, the vision of a confederacy appeared to Deganawidah, a Huron boy born in what is now Ontario, known as the Great Peacemaker. They brought a message, known as the Great Law of Peace. There was constant warfare between the tribes mainly for revenge for murder. Deganawidah with the help of Hiawatha, an Iraqi warrior and also a good speaker, Hiawatha, visited all the tribes to explain the aims of the confederacy. When the Onondaga nation refused to join it, Deganawidah installed the seat of the confederacy on their land so that they had to join. After the Tuscarora nation joined the League in the 18th century, the Iroquois have often been known as the Six Nations. The League is embodied in the Grand Council, an assembly of fifty hereditary sachems.

Women had an important role in the confederacy. They chose the delegates to the central council from the 49 lineages from the five nations, a lineage, which was hereditary through the mother line. Women had their own council that advised the central council. They had the power to veto war or to modify decisions about relation with other nations. Although the confederacy made war with other nations, they kept peace between themselves for nearly 300 years that is until it broke apart because of rivalries with the French and the English.

When Europeans first arrived in North America, the Iroquois were based in what is now the northeastern United States, primarily in what is referred to today as upstate New York. Today, Iroquois live primarily in the United States and Canada.

The Iroquois League has often also been known as the Iroquois Confederacy, but some modern scholars now make a distinction between the League and the Confederacy. According to this interpretation, the Iroquois League refers to the ceremonial and cultural institution embodied in the Grand Council, while the Iroquois Confederacy was the decentralized political and diplomatic entity that emerged in response to European colonization. The League still exists, but the Confederacy was shattered by the defeat of the British and allied Iroquois nations in the American Revolutionary War.

2.9.1 Name

The Iroquois also refer to themselves as the Haudenosaunee, which means “People of the Longhouse,” or more accurately, “They Are Building a Long House.” The term is said to have been introduced by The Great Peacemaker at the time of the formation of the League. It implies that the nations of the League should live together as families in the same longhouse. Symbolically, the Seneca were the guardians of the western door of the “tribal longhouse” and the Mohawk were the guardians of the eastern door. The Onondagas, whose homeland was in the centre of Haudenosaunee territory, were keepers of the League’s (both literal and figurative) central flame.

The name “Iroquois” was bestowed upon the Haudensosaunee by the French and has several potential origins:

• A possible origin of the name Iroquois is reputed to come from a French version of irinakhoiw, a Huron (Wyandot) name—considered an insult—meaning “Black Snakes” or “real adders”. The Iroquois were enemies of the Huron and the Algonquin, who allied with the French, because of their rivalry in the fur trade.

• The Haudenosaunee often end their oratory with the phrase “hiro kone”; hiro translates as “I have spoken”, and kone can be translated several ways, the most common being “in joy”, “in sorrow”, or “in truth”. Hiro kone, to the French encountering the Haudenosaunee, would sound like “Iroquois.

• Another version is that “Iroquois” would derive from a Basque expression, Hilokoa, meaning the “killer people”.

2.9.2 History – Formation of the League

The Iroquois moved to the south in long wars of invasion in present-day Kentucky. According to one theory, it was the Iroquois who, by about 1200, had pushed tribes of the Ohio River valley, such as the Quapaw (Akansea) and Ofo (Mosopelea) out of the region in a migration west of the Mississippi River. By the mid-17th century, these Siouan groups had settled in their historically known territories of the Midwest, with some displacing other tribes to the west in their turn.

The Iroquois League was established prior to major European contact. Most archaeologists and anthropologists believe that the League was formed sometime between about 1450 and 1600. A few claims have been made for an

earlier date; one recent study has argued that the League was formed in 1142, based on a solar eclipse in that year that seems to fit one oral tradition.

According to legend, an evil Onondaga chieftain named Tadodaho was the last to be converted to the ways of peace by The Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha. He became the spiritual leader of the Haudenosaunee. This event is said to have occurred at Onondaga Lake near Syracuse, New York. The title Tadodaho is still used for the league’s spiritual leader, the fiftieth chief, who sits with the Onondaga in council. He is the only one of the fifty to have been chosen by the entire Haudenosaunee people. The current Tadodaho is Sid Hill of the Onondaga Nation.

2.9.3 Culture

2.9.3.1 Melting pot

The Iroquois are a melting pot. League traditions allowed for the dead to be symbolically replaced through the “Mourning War”, raids intended to seize captives to replace lost compatriots and take vengeance on non-members. This tradition was common to native people of the northeast and was quite different from European settlers’ notions of combat.

The Iroquois aimed to create an empire by incorporating conquered peoples and remolding them into Iroquois and thus naturalizing them as full citizens of the tribe. By 1668, two-thirds of the Oneida village were assimilated Algonquians and Hurons. At Onondaga there were Native Americans of seven different nations and among the Seneca eleven.

2.9.3.2 Food

The Iroquois were a mix of farmers, fishers, gatherers, and hunters, though their main diet came from farming. The main crops they farmed were corn, beans and squash, which were called the three sisters and were considered special gifts from the Creator. The cornstalks grow, the bean plants climb the stalks, and the squash grow beneath, inhibiting weeds and keeping the soil moist under the shade of their broad leaves. In this combination, the soil remained fertile for several decades. The food was stored during the winter, and it lasts for two to three years. When the soil eventually lost its fertility, the Iroquois migrated.

Gathering was the job of the women and children. Wild roots, greens, berries and nuts were gathered in the summer. During spring, maple syrup was tapped from the trees, and herbs were gathered for medicine.

The Iroquois mostly hunted deer but also other game such as wild turkey and migratory birds. Muskrat and beaver were hunted during the winter. Fishing was also a significant source of food because the Iroquois were located near a large river. They fished salmon, trout, bass, perch and whitefish. In the spring the Iroquois netted, and in the winter fishing holes were made in the ice.

2.9.3.3 Wampum

Since they had no writing system, the Iroquois depended upon the spoken word to pass down their history, traditions, and rituals. As an aid to memory, the Iroquois used shells and shell beads. The Europeans called the beads wampum, from wampumpeag, a word used by Indians in the area who spoke Algonquin languages.

The type of wampum most commonly used in historic times was bead wampum, cut from various seashells, ground and polished, and then bored through the centre with a small hand drill. The purple and white beads, made from the shell of the quahog clam, were arranged on belts in designs representing events of significance.

Certain elders were designated to memorize the various events and treaty articles represented on the belts. These men could “read” the belts and reproduce their contents with great accuracy. The belts were stored at Onondaga, the capital of the confederacy, in the care of a designated wampum keeper.

Famous wampum belts of the Iroquois include the Hiawatha Wampum, which represents the original Five Nations, the spatial arrangement of their individual territories, and the nature of their roles in the Confederacy. The modern Iroquois flag is a rendition of the pattern of the original Hiawatha Wampum belt. The Two Row Wampum, also known as Guswhenta, depicts the agreement made between the Iroquois League and representatives of the Dutch government in 1613, an agreement upon which all subsequent Iroquois treaties with Europeans and Americans have been based.

2.9.3.4 Women in Society

When Americans and Canadians of European descent began to study Iroquois customs in the 18th and 19th centuries, they observed that women assumed a position in Iroquois society roughly equal in power to that of the men. Individual women could hold property including dwellings, horses and farmed land, and their property before marriage stayed in their possession without being mixed with that of their husband’s. The work of a woman’s hands was hers to do with as she saw fit. A husband lived in the longhouse of his wife’s family. A woman choosing to divorce an unsatisfactory husband was able to ask him to leave the dwelling, taking any of his possessions with him. Women had responsibility for the children of the marriage, and children were educated by members of the mother’s family. The clans were matrilineal, that is, clan ties were traced through the mother’s line. If a couple separated, the woman kept the children. Violence against women by men was virtually unknown.

The chief of a clan could be removed at any time by a council of the mothers of that clan, and the chief’s sister was responsible for nominating his successor.

2.9.3.5 Spiritual Beliefs

In the Iroquois belief system was a formless Great Spirit or Creator, from whom other spirits were derived. Spirits animated all of nature and controlled the changing of the seasons. Key festivals coincided with the major events of the agricultural calendar, including a harvest festival of thanksgiving. After the arrival of the Europeans, many Iroquois became Christians, among them Kateri Tekakwitha, a young woman of mixed birth. Traditional religion was revived to some extent in the second half of the 18th century by the teachings of the Iroquois prophet Handsome Lake.

2.9.4 People and Nations

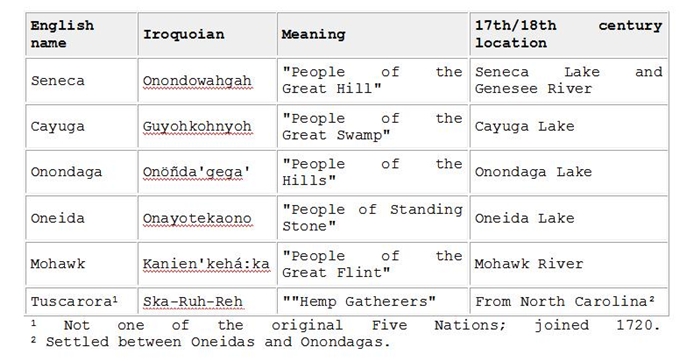

The first five nations listed below formed the original Five Nations (listed from west to north); the Tuscarora became the sixth nation in 1720.